A post by Lea Doobe, Mateusz Zawadzki, Muhammad Ahmer and Nina Huber

Agrobiodiversity is often presented as the key to resilience when it comes to climate change. But how much diversity can one farm really handle? At Hof Tolle in Northern Hesse, diversity is practiced every day, showing both its potential and its challenges.

First impressions

When we stepped off the train, Hof Tolle welcomed us with a warm atmosphere: a little self-service café on the right, a colorful market garden on the left. Right away, we had the feeling that this farm was different. Hof Tolle does not just concentrate on one activity but on many at once. Crops, vegetables, cattle, trees and even education are combined. Diversity is the main strategy for adapting to climate change, but it also means a lot of work to keep everything going.

Farming on difficult soils

The soils on the farm are loamy, stony and poor in nutrient availability. In response, the team diversifies its crop production with spelt, barley for brewing, oats, legumes like chickpeas. Strategies include crop rotation, intercropping and cover crops. Each crop adds resilience to the system and helps balancing risks, especially under changing weather conditions. But it also means more planning and more tasks to manage.

Vegetables for people and biodiversity

The market garden is one of the farm’s most meaningful branches. In beautifully arranged stripes, a large variety of vegetables is grown and sold directly to customers in vegetable boxes. The system generates about a quarter of the farm’s income from a small fraction of the land, increases biodiversity and connects people to the farm. But it also requires daily attention, making it one of the most work intensive parts of the farm.

Cattle and trees for resilience

Cattle form another branch. A herd of around 25 young animals grazes extensively on meadows, keeping landscapes open for biodiversity. Through mob grazing, the herd is moved regularly, improving soil and plant diversity [1]. This grazing strategy works well for the environment and shows how animal husbandry can actively support ecosystem services. And in addition to all this, Hof Tolle has also planted its first agroforestry system, adding trees as another element of resilience [2].

The challenge of diversification

Looked at separately, each branch is meaningful and contributes a lot to resilience: vegetables bring diversity to diets, cattle preserve landscapes, agroforestry protects soils and help retain water, crop rotations benefit the soil. However, managing all these branches in parallel is highly demanding and means a lot of work. Research confirms this dilemma: diversification can buffer risks and build resilience, but too much diversification across branches can push the limits of available labor [3]. Hof Tolle illustrates this reality and shows why such efforts deserve more recognition and support.

Lessons and outlook

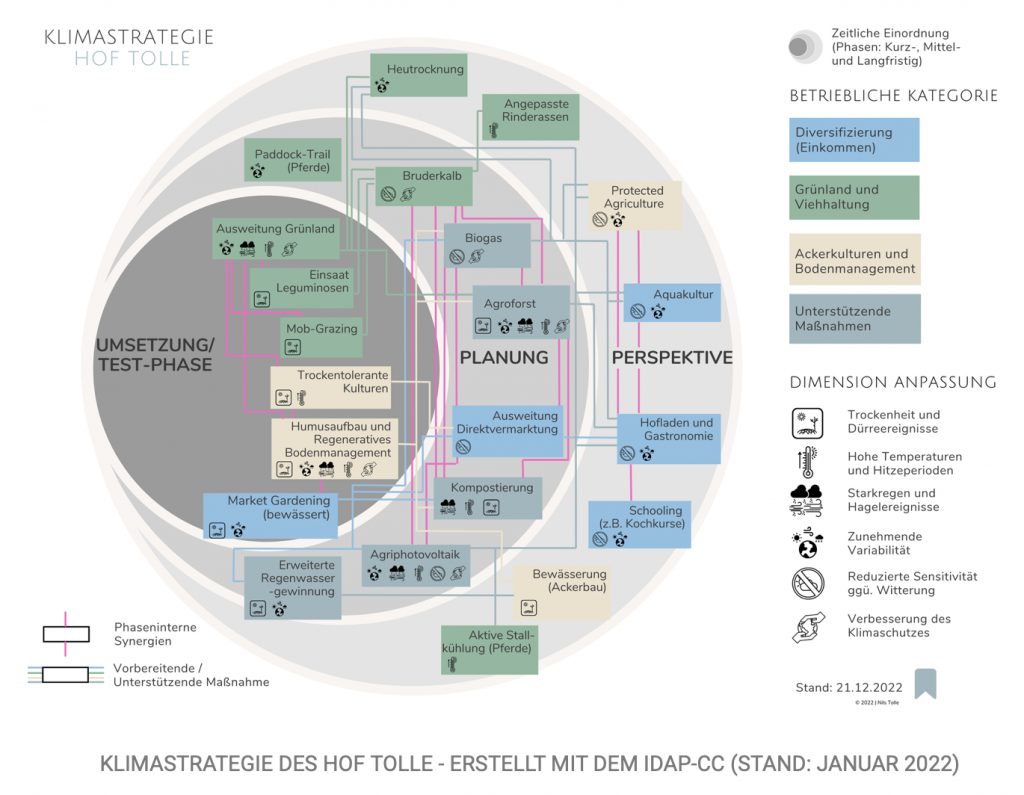

The farm is run on a part-time basis and is not yet financially profitable. Still, it provides important lessons in climate adaptation and agrobiodiversity, offering an example of what farming systems of the future might look like. The whole system, including today’s measures as well as future ones, is selected carefully and sculptured into a holistic climate adaptation strategy. To serve as a model, farms like Hof Tolle need better frameworks and policy support, so that innovation and environmental care not come at the cost of personal overload.

In the meantime, customers could be invited to take part in tasks such as weeding days, making the farm even more of a collective project. Volunteers could be included to help with some tasks on the farm. On the technical side, trials with biochar could help improve soil fertility [4] and help with marginal soils.

During our visit we learned that diversification like it is practiced on Hof Tolle is both a strength and a challenge. The future of farming may depend on how much we value and support farms like this one, so that they can continue to inspire and work on solutions for changing conditions.

This blog post was written as part of the “Agrobiodiversity Summer School” in Germany in August 2025. This summer school is a cooperation project between the ZHAW Institute of Natural Resource Sciences, the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture in Switzerland and Germany (FiBL) and is supported by the Mercator Foundation Switzerland.

References

[1] Billman, E.D. et al. (2020). Mob and rotational grazing influence pasture biomass, nutritive value, and species composition. Agronomy Journal, 112, 2866-2878.

[2] Quandt, A. et al. (2023). Climate change adaptation through agroforestry: opportunities and gaps. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability.

[3] Darnhofer, I. & Strauss, A. (2014). Resilience of family farms: understanding the trade-offs linked to diversification.

[4] Joseph, S. et al. (2021). Biochar in problematic soils: A review. Soil Use and Management.