A post by Artur Falcette, Adèle Garret, Robert Mäntler and Dominique Schwarz

How Slovenian salt makers have been thriving for 700 years at protecting biodiversity

Salt production in coastal regions, an activity that involves the transformation of natural coastal areas into salt flats, can generate significant environmental and social impacts. The conversion of ecosystems such as mangroves and wetlands into salt production areas can lead to biodiversity loss, degradation of critical habitats, and changes in local ecological dynamics, which negatively affects fauna and flora [1]. In addition, soil salinization and contamination of water resources due to inadequate management of salt flats can compromise water quality, affecting both ecosystems and human communities dependent on these resources [2]. Socially, the expansion of salt flats can generate conflicts over land and water use, as well as impact the traditional ways of life of communities that depend on fishing and subsistence agriculture for their survival [3].

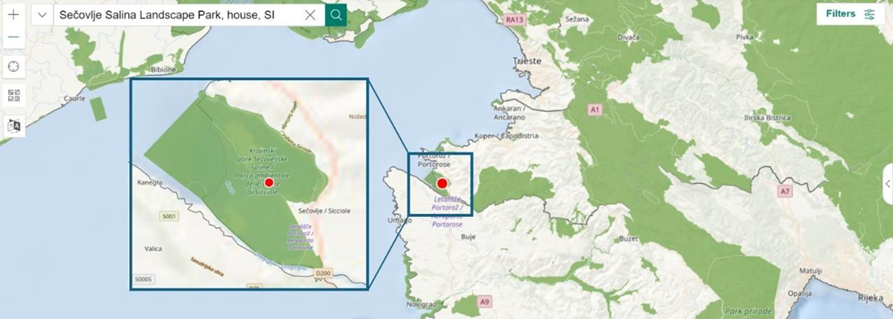

Withstanding modern salt mining, Piran Saline (Piranske Soline), has been producing salt in a traditional way for over 700 years on the coast of the country in one of its largest natural parks. Sečovlje Salina National Park (750 hectares) is located at the southern end of the coast of Piran Bay, in the estuary of the Dragonja River. Over the centuries, the deposition of sediments has formed an alluvial coastal plain, where about 700 years ago tanks were created for the evaporation of seawater. The landscape and ecosystem of the region, which depend on both the saline environment and human presence, are home to several species of flora and fauna, especially birds, halophilous plants and white shrimp, adapted to hypersaline conditions [4].

Although not considered farming but mining, salt production guarantees the possibility of diversification in the use of landscape on the coast of Slovenia, being added to the productive structure of the region, which also profits from fishing and tourism.

By mining in a traditional way for 700 years, using as little equipment as possible, handcraft knowledge is maintained over the generations, being incorporated into the culture of the region. It is important mentioning that, on the other hand, the harsh working condition in mining is keeping the new generations away.

The company was able to add value to its product while also diversifying its application. In addition to traditional salt, they produce fleur de sel, spiced salt, salted pumpkin seeds and various cosmetic products, such as face masks made from the mud of the salt flat that can be purchased in store or online. They also own a spa, museum and sell guided tours.

Such production, in addition to introducing the company’s products along different food chains and systems, makes it possible for different profiles and generations of workers to be hired. Also, being a part of Natura 2000 allows the company to strengthen the relationship with researchers, policy makers and different stakeholders throughout its chain.

And what if? What if each salt mining site, each farm, each hectare of cereals and each field of vegetables would care for their pinch of biodiversity?

This blog post was written as part of the “Agrobiodiversity Summer School” in Slovenia in August 2024, as a cooperation project between the ZHAW Institute of Natural Resource Sciences, the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture in Switzerland (FiBL) and the Biotechnical Faculty of University of Ljubljana nd is supported by the Mercator Foundation Switzerland.

References

- KUMARAVEL, R.; SWARNA LATHA, P.; JANARTHANAN, S. Environmental impacts of salt extraction processes: a case study from South India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, v. 14, n. 6, p. 584-595, 2017. ↩︎

- SIVAKUMAR, K.; KARTHIK, R.; RAJESH, P. S. Impact of salt pan effluent on the physicochemical characteristics of ground water in Tuticorin, South India. Desalination and Water Treatment, v. 128, p. 320-328, 2018. Sečovlje Salina Nature Park (n.d.). Retrieved from www.kpss.si, last accessed on Oct 11th 2024. ↩︎

- HANNAN, M. A.; BEGUM, S. Salinity intrusion and livelihood strategies of coastal people in Bangladesh. Environmental Science & Policy, v. 102, p. 162-169, 2020. ↩︎

- Sečovlje Salina Nature Park (n.d.). Retrieved from www.kpss.si, last accessed on Oct 11th 2024. ↩︎