By Nico Ebert (ZHAW)

cross-posted from the author’s blog

Many Internet users inside and outside the European Union are very familiar with cookie banners: they pop up on websites, they are often annoying, and it is tedious to really deal with them. Having to state our data sharing and protection preferences over and over again is a questionable concept by itself. But even if we accept the concept of cookie banner as a matter of fact our behavior towards them seems paradox at a first glance.

It has long been known that some of the tracking techniques used are very privacy invasive (e.g. session replay, fingerprinting), behavioral data is exchanged between different websites, advertising marketers and social media operators and extensive user profiles are created. At the same time, the benefits of cookies appear to be minimal. Why should we be willing to support companies with our data for “usability”, “marketing” or “social media” purposes if we seem to get nothing in return? And yet we “accept all cookies” all the time…

There is obviously a conflict of interest for those that ask for our consent in our browsers: companies need our behavioral data, so why should websites actively help us to prevent data collection? On our smartphones, this conflict is resolved by the fact that the operating system acts as a proxy for our interests against the app’s other interests. Just imagine the “very convincing” user interface dialogue in which a freemium game itself would ask you for the permission to download your address book and photos of your daughter.

Having accepted this conflict of interest what is actually happening when we interact with a cookie banner? There are many theoretical ways to explain our behavior. While some theories assume rational behavior (e.g. weighting benefits vs. costs of accepting cookies), other don’t (e.g. nudging us to accept cookies by default settings and hard to find opt-out option). One explanation offers the protection motivation theory (PMT) from Rogers (1975) which does not assume rationality. PMT’s origin lies in disease and health prevention and it wants to facilitate a protection motivation (e.g. to quit smoking) by establishing a pervasive form of communication (e.g. creating fear with lung cancer photos on cigarette boxes, practical information on how to quit smoking).

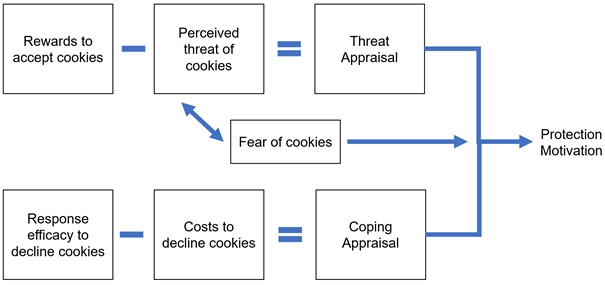

The figure shows the cognitive mediating process of the revised PMT from 1983 adapted to the field of cookie consent decision. Theoretically, a positive appraisal of the threats posed by cookies and the fear of cookies as well as a positive appraisal of the handling of cookies would lead to an individual motivation to protect oneself from cookies and ultimately result in the rejection of cookies. In practice, cookie dialogues try to avoid any kind of threat perception and fear creation. Information that could be alarming for privacy sensitive users is often many clicks away: that the site uses fingerprinting, session replays and shares your data with Tiktok is hidden deep within the cookie policy in legal language. Instead, sometimes even euphemisms are used in communication that refer to the cookies your grandma baked. While threat and fear are avoided, rewards for accepting cookies are mentioned: “help to improve the website” and “personalized offers”. The result is a negative thread appraisal.

Most people would agree that it is quite difficult to deal with cookie dialogs in such a way that all non-technically required cookies are rejected. Several recent studies have shown that the costs to declining cookies are high compared to accepting cookies. Costs can be measured in time, clicks, saliency of options to name a few. The “choice architecture” that describes how a cookie consent dialogues is designed is sometimes not in our favor. “Dark patterns” make it easy to “accept all” and make it difficult to “decline all”. The result is a negative coping appraisal.

Ultimately, negative coping and threat appraisal do not lead to a motivation for behavior to protect one’s privacy. As a result, also critical people click “accept all”.

For sure, many people wouldn’t perceive cookies as threats even if they would fully understand what data is collected and how it is used. Many people probably like personalized services and ads. Nobody is publicly known that has ever died of accepting cookies. However, maybe other people would decline cookies if they would be aware of threats and declining cookies was easier.

References

Floyd, D. L., Prentice‐Dunn, S., & Rogers, R. W. (2000). A meta‐analysis of research on protection motivation theory. Journal of applied social psychology, 30(2), 407–429.

Ruiter, R. A., Kessels, L. T., Peters, G. J. Y., & Kok, G. (2014). Sixty years of fear appeal research: Current state of the evidence. International journal of psychology, 49(2), 63–70.